Saving Private Ryan Is Based on the True Story of Four Irish American Brothers

Posted by Adam Farley on 6th Jun 2019

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the allied landing at Normandy during World War II, otherwise known as D-Day, masterfully and viscerally portrayed on screen in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan. The film marked a turning point in cinema history, permanently changed how war movies were made and shot. It was so realistic, in fact, that the U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs established a national hotline for former service members to call if they experienced emotional distress from the movie.

But its portrayal of the horrors of war in general wasn’t the only realistic thing about it. The storyline itself — about Captain John H. Miller (Tom Hanks) leading a group of Army Rangers to find and retrieve Private James Francis Ryan (Matt Damon) to send him home following the death of his three brothers on D-Day — is ripped straight from the true story of the Niland brothers, Irish Catholic siblings from upstate New York.

THE REAL PRIVATE RYAN

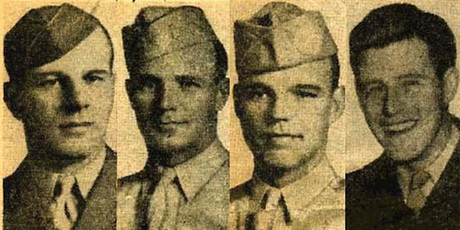

The real Private Ryan was actually named Frederick Niland, though everyone called him Fritz. Fritz was born in 1920 in Tonawanda, New York, just north of Buffalo along the Niagara River, the youngest of six siblings, including four brothers. Two of Fritz’s older brothers, Robert and Preston, had enlisted in the Army prior to the entrance of the United States in the war, while Fritz and his third brother Edward enlisted in November 1942.

At the time, the U.S. War Department had just enacted what was called the “sole survivor policy,” or Directive 1315.15 Special Separation Policies for Survivorship, which exempted from service lone surviving family members. The policy was a direct response to the deaths of the five Sullivan brothers, also Irish American, who were aboard the U.S.S. Juneau when it was torpedoed and sunk during the Battle of Guadalcanal. After that point, no family members would be placed in the same units to help avoid a tragedy like the Sullivan brothers. As a result, Robert was placed with the 82nd Airborne Division, Preston with the 4th Infantry Division, Edward became a pilot with the U.S. Army Air Corps, and Fritz joined the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division. Edward was sent to the Burma-India-China theater while Robert, Preston, and Fritz all awaited the invasion of Normandy in England.

THE SOLE SURVIVOR

Fate was unkind to the Niland family. In May 1944, parents Michael and Augusta received word that Edward had been shot down over Burma and was missing in action, presumed dead. It’s not clear if the other three brothers received word prior to the D-Day invasion, but by the end of June 6, Robert would also be dead, and Preston a day later.

Robert had parachuted into France near the town of Sainte-Mère-Église, which was secured by the 3rd Infantry Battalion that morning, and was sent to establish a perimeter defense in the village of Neuville-au-Plain. While under fire from two German companies during a counter attack, Robert manned a machine gun with two other men to buy time for a retreat back to Ste. Mere-Eglise. The two men managed to escape, but Robert was mortally wounded.

Today, a paratrooper memorial on the church of Sainte-Mère-Église commemorates all D-Day paratroop infantrymen who liberated the town in 1944. The memorial is modeled after the story of John Steele, who landed on the tower of the church when his parachute became stuck in the stonework.

Preston, along with the 4th Infantry Division, had landed on Utah Beach on D-Day. Though the division suffered relatively minor casualties during its initial invasion, more fighting to clear German batteries beyond the sand was to come. On June 7, Preston was tasked with securing the Crisbecq battery, notable for having sunk the U.S.S. Cory the previous day. Preston was killed in the battle and his unit forced to retreat. It would be almost a week before the battery was eventually captured by the 9th Infantry Division.

Fritz himself fought through the first days following the invasion. His battalion, the 3rd, was meant to be a reserve parachute unit, but misdrops on D-Day meant that he was forced to fight his way to safety. (If you’ve seen Spielberg’s other WWII work Band of Brothers, you probably have a sense of how prevalent misdrops were on D-Day.)

Thus, within the course of less than a month, Michael and Augusta Niland had received three death notices, their only condolence, according to a July 8, 1944 article about the tragedy in the Buffalo Evening News, was a letter from Fritz letting them know “Dad’s Spanish-American War stories are going to have to take a backseat when I get home.”

SENDING FRITZ NILAND HOME

Though the movie Saving Private Ryan depicts an epic odyssey of urban warfare in search of a missing James Ryan, the real-life Niland was found with relative ease. Once the War Department was informed of the three brothers’ deaths, it put in orders for Fritz to be located and shipped home. Fr. Francis Sampson, a chaplain with the 501st, was the man responsible for the job and soon found Fritz with relative ease.

Fritz had relayed with the 82nd Airborne in hopes of uniting with his brother Robert when he was informed of his death, along with Preston’s. Fr. Sampson was alerted to Fritz’s presence and put in the paperwork to send him home. Fritz would spend the remainder of the war in New York serving as an MP and was awarded the Bronze Star for his service.

Fritz died in 1983 and is buried at Fort Richardson National Cemetery in Tonawanda. His brothers Robert and Preston are buried side by side at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer.

As for Edward, it turned out that he was not actually killed in the war as his family (and the War Department) had assumed. When his plane went down, he was captured by Japanese forces after having spent several days lost in the jungle and interned at a POW camp in Burma. He was released when British soldiers liberated the camp in May 1945 and spent the rest of his life in Tonawanda and died in 1984.

SAVING PRIVATE RYAN AND IRELAND

Filming restrictions at Omaha Beach meant that the landing scenes had to be shot elsewhere. Spielberg wanted as exact a location as possible for the scenes and eventually landed on Ballinesker Beach, Curracloe Strand, County Wexford, where the long sandy strand abuts tall bluffs, nearly identical to those at Normandy. To achieve a realistic effect, more than 1,500 extras were used during filming to portray both Allied and German troops, the majority of whom were members of the Irish Reserve Defense Force.

H/T: GIJobs.com and History for detailing this history previously. More information about the Niland brothers and Fr. Sampson can be found in Stephen Ambrose’s 1992 book Band of Brothers, upon which the miniseries of the same name is based.