The Arts & Crafts Movement in Ireland & the Flowering of a New Artistic Culture

Posted by Allison Krier on 7th Nov 2018

“The idea is to make beautiful things...Everything as far as possible, is Irish.” This declaration by Susan Pollexfen Yeats in 1903 regarding the Dun Emer Guild is at the heart of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland. Beginning in the 1890s through the 1920s, Ireland experienced a vibrant cultural renaissance that was fueled by the desire to fashion distinctively Irish creations of excellent quality. This blossoming was transformative and intertwined with the social and political concerns of the time: a desire for Irish independence and Home Rule, and a nationalistic pride that required a crafting of a cultural identity. Notions of the past and a vision for a better future began to meld.

The Arts and Crafts Movement emerged in England in the latter half of the nineteenth century and was a direct reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the modern, particularly urban, society that immediately evolved from it. The basis of the movement emphasized the artist/artisan/designer’s point of view and regarded the maker’s relationship to material, process, technique, and iconography. In other words, hand craftsmanship was championed over the cheap and often shoddy goods that resulted from mechanized mass production. A desire to dissolve the hierarchal status between what became known as the fine arts—easel painting and sculpture—and the less revered applied or decorative arts—the craft and design disciplines—also became a motivating factor.

The decorative arts include everything from vernacular stained glass to everyday tableware. These Irish Crafts mugs are a contemporary take on that homespun tradition.

Critic and historian John Ruskin was the first to articulate what would become the foundational theory of the Arts and Crafts Movement with the 1853 publication of his three-volume treatise The Stones of Venice. The study provided an exhaustively detailed chronicle of Venetian architecture describing over eighty churches and buildings in the Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance styles. In volume two, “The Nature of Gothic” illustrates Ruskin’s point of view that the imperfections observed in the City’s Gothic architectural ornament demonstrated the humanity in its creation whereas something slick and perfect is an example of dehumanization. This perspective provided the underpinnings for the Arts and Crafts Movement and greatly affected Ruskin’s notable and eminent student at Oxford, William Morris, the leader of the movement and one of the most influential figures in nineteenth-century arts and on early twentieth-century design.

William Morris was an artist, a poet, a publisher, a theoretician, an entrepreneur, a preservationist, and a reformer. For Morris, the movement was more than merely advocating the means of production for artistic goods, it was also a way a life. He lamented for the bygone pre-industrial society and fetishized the medieval era, which he believed to be a time where the world was uncorrupted by industrialism and capitalism and individuals could lead a more honest lifestyle. For many in England, the Middle Ages were romanticized for its notions of knights and chivalry, courtiers, and old English mystical lore. English national pride also framed this reflection on the past, and there is a quaint charm to its allure, which significantly resonated in a rapidly changing and increasingly faster-paced lifestyle of the 19th century. In Ireland, although more agrarian and rural than England, concerns were similar, echoed in a widespread preoccupation with Early Christian-Celtic past as well as ancient Hibernia. These fixations visually transcended to the contemporary artistic production of the time with revival styles and a revival of craft techniques.

“Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful,” Morris declared. His views on living extended to the linking of ideals about aesthetics to utility. Despite his abhorrence for contemporary life, this was a modern revelation. The furnishings created for his newly built home, Red House (completed 1860), southeast of London in Bexleyheath, looked to humble vernacular models. Unique designs of simple forms and regional materials, often painted with scenes and motifs of the Middle Ages or Renaissance, or beautiful patterns derived from nature, set a mode. They were artist’s objects. This philosophy and creative output inspired numerous artists and many endeavors, both private and organizational, throughout Britain, Europe and America. In Ireland this included guilds such as the Dun Emer, The Royal Society of Dublin, which held several exhibitions, and the Dublin School of Art.

The domestic arts provided the first opportunities to develop exceptional Irish craftsmanship and so women were at the forefront of the movement. The Dun Emer Guild was a driving force in the Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland. Founded in 1902 by Miss Evelyn Gleeson, the Guild had the financial backing of her friend Alexander Miller. Gleason studied painting and portraiture in London and was highly skilled in the textiles arts. The Yeats sisters, Lily (born Susan Mary), who had been an embroidery assistant to William Morris’s daughter Mary, and Lolly (born Elizabeth), an astute painter and instructor, joined soon after the Guild’s founding. Central to the Guild was that the designs must be of the spirit and traditions of the country. Already there had been a patriotic impetus to revive traditional textile craft methods in the nineteenth century by educating young women of impoverished communities so that they may earn a decent wage for their skilled output. (Notably, this project, run by the Congested Districts Board, is responsible for the Aran sweaters we know today.) It became the civic duty of upper class and wealthier women to purchase the Irish textiles for display in the home. The design of the carpets made at Dun Emer show patterns of curving Celtic motifs of which some showed a relationship to the sinuous curves of the Art Nouveau style.

Many contemporary jewelry pieces are inspired by the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau, like this Gold Plated Black Irish Tara Brooch from Solvar.

Although distinguished for its textile crafts straightaway, by 1904 Dun Emer extended its repertoire to other crafts such as bookbinding, metalworking and enameling. Also of celebrated prominence was its press workshop, Cuala, led by Lolly Yeats. Ireland’s literary tradition is a profound one and this is no exception. The sisters’ better-known brothers were involved too. William Butler Yeats acted as editor and became interested in the design and layout of the printed material, particularly books. Influenced by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, for which he had visited and met Morris, Yeats believed that a book could be a work of art beyond the prestige of the written word. Special copies of his In the Seven Woods: Being Poems Chiefly of the Irish Heroic Age, 1903, were printed at Cuala with artistic attention to typeface and page layouts. Unlike the dense page compositions of the Kelmscott Press, which directly drew from medieval illuminated manuscripts, the design for Seven Woods is more restrained with a modern feel. Jack Yeats, a talented and expressive painter, designed frontispieces for Cuala and Lolly created many layouts. After a falling out with Gleason, Lily and Lolly Yeats left Dun Emer but Cuala did persist, as did the Guild. Dun Emer closed upon Gleeson’s death in 1944.

In the north of Ireland, the storied history of Limerick lace has a chapter in the Arts and Crafts Movement as well. Limerick lace production became fully industrialized by the 1850s. Unlike much of Ireland, Belfast, and some the area surrounding the city such as County Limerick, was industrialized. When most of the large factories collapsed, there was a desire to resurrect traditional lace handiwork in the 1880s. The Arts and Crafts Movement supported this. It was an opportunity to redefine the culture and address the poverty issue that plagued Ireland. Women could earn a high wage and work out of their homes by sewing expertly crafted lace as well as participate in an ideal of Irish authenticity of handcraft over the mimicry of mass production. Beyond affluent women, who relished it as a symbol for Irish femininity and refinement, ecclesiastical men helped create a significant market and one that transcended ideas of gender. Priests often wore robes adorned with lace. Today, Limerick lace continues to enjoy status as a symbol of Irish culture as well as other textiles such cable-knit apparel.

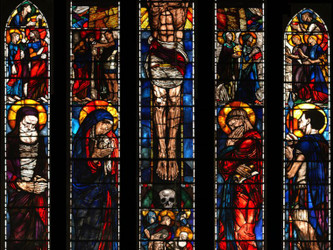

Works of remarkable achievement in the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement occur with the making of stained glass works. Two pioneering and progressive artists, Harry Clarke and Wilhelmina Geddes demonstrated not only mastery of the craft, but also a keen ability to use the traditional discipline as a means for portrayals in the modern idiom. Their designs, mostly for ecclesiastical milieus and of biblical or historical topics, exhibit imaginative interpretations of a contemporary mood and style. Geddes, born in the North in County Leitrim, learned the craft in Dublin and her painterly expertise generated a provocative use of color creating vivid pictorials that are emotively brooding, even edgy. Her first solo work, a small-scale triptych made in 1911, depict scenes from the Life of Saint Colman MacDuagh of Galway. Her painterly adeptness with bold but strategic brushwork yields an expressive rendering of the topic. Both Geddes and Clarke delved into meticulous antiquarian research for their projects and commissions, which provided for modern masterpieces deemed to be especially of an Irish character. Hiberno-Romanesque architecture punctuates the landscape throughout Ireland and offered romantic inspiration especially for structurally integrated stained glass. The picturesque buildings were authentic relics, simple stone edifices with rounded arches and pointed triangular forms and rooflines, that truly aided to define a new Irish identity and impacted the Irish movement across all cultural spheres.

Irish stained glass flourished in the Arts and Crafts Movement. Today, Royal Tara carries on that tradition in their collection of panels for the home.

The Honan Chapel windows at the University College in Cork, 1916, by Harry Clarke are one of the great gems of the Irish Arts and Craft. Clarke depicted three saints together as a work: Patrick, Brigit and Colmslie as well as another window showing St. Gobat. Not only are they a triumph of Clarke’s skill with the medium, the windows reveal his artistic sensibilities and his awareness and experimentation with avant-garde movements such as Expressionism and French Symbolism. His compositional design for the smaller-scaled installation exploits the material for a bejeweled and dazzling effect. Clarke’s fantastical, ethereal and stylized figures expose his psychological perceptions, a perceptive pathos reacting to a changing world where feelings of alienation and fragmentation created angst for modern society. His dreamy depictions can also be interpreted through the tradition of the grotesque where bizarre, and sometimes dark outlandish humor, make for unnerving imagery. Saint Gobnait’s attenuated and abstracted form amidst Byzantinesque mosaic-like motifs reveals an affinity for the Expressionism that flourished in Vienna, and specifically here, a simpatico with the paintings of Gustave Klimt.

Honan Chapel not only commissioned grand church windows, they supported the Arts and Crafts Movement with numerous commissions and purchases. Their collection, partly held at the University College in Cork, encompasses superbly woven tapestries by Evelyn Gleeson and Katherine MacCormack, also of Dun Emer, and exquisite ecclesial robes designed by Ethel Josephine Scally. Scally’s designs uphold the nationalistic ethos of the movement with motifs derived from the Early Christian-Celtic era and were made using silk, gold threads and acetate cloth. The Book of Kells was particularly influential to her designs. The Chapel collection would not be complete without expertly made objects of Irish metalsmithing. Chalices, crosses, and candlesticks, primarily of silver, some gold, and semi-precious stones incorporated interlacing Celtic bands and motifs often along with Christian iconography and played a major role in the religious rituals and the eminence of the Chapel. Silver Irish marriage cups, still a tradition today, apply similar decorative Celtic designs.

Many wedding chalices made today still bear the hallmark designs of the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement such as Celtic knot designs and ornamented handles. (Mullingar Pewter Claddagh Wedding Cup)

The Irish Arts and Crafts Movement fostered great accomplishment in visual culture. In the crafting of artistic goods and symbols of the old, came the establishment of a new Irish identity, regenerated for the modern era.